January 18, 2022

By Kostas Pliakos – CNN Greece

In the small harbour of La Goulette, Tunis, from which small and medium sized vessels set out for their fishing trips in the Mediterranean, Mohammed is cleaning his nets. He is one among hundreds of fishermen in Tunisia, who takes to the sea almost daily to fish the coastal or inshore waters.

Mohammed is also one of the dozens of fishermen in Tunisia – and the Mediterranean in general – that are being trained to tackle the incidental capture in fishing gear of vulnerable, non-commercial species (also known as “bycatch”). These can include sea turtles, sharks and rays, marine mammals, sea birds, corals, and sponges.

“In the past, whenever a dolphin was caught in our nets, we were glad, because they damage our fishing nets and drive off the larger fish. It was the same for sea turtles. When we caught a sea turtle in our nets, we killed it, ate its flesh and used its fat as an ointment for skin irritations. We didn’t know back then how important these creatures are to our livelihoods and to the balance of the sea. I regret the things we did back then but we didn’t know any better. Now, when we happen to catch a dolphin or a sea turtle, we immediately release it back into sea”

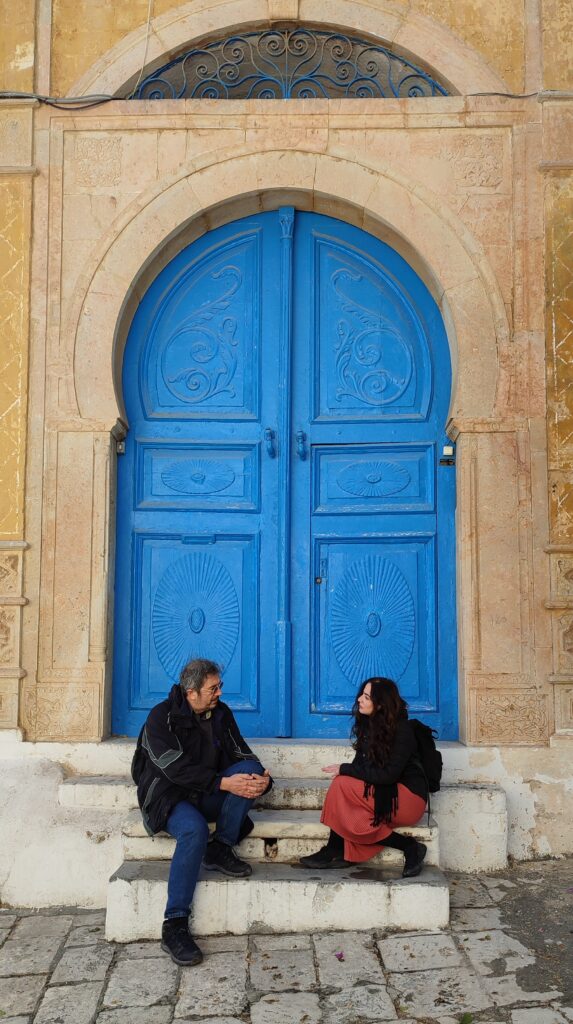

©CNN Greece, photo Lefteris Partsalis

Bycatch has become a true menace to the seas. Particularly at a time when the overfishing of a number of species means some populations are nearing collapse, and pollution from land-based wastewater, chemicals and especially plastics (that can find their way into the food chain) has reached crisis level, bycatch is delivering a final blow to marine ecosystems.

We were in Tunisia for CNN Greece, as the country is one of five Mediterranean ones in which an ambitious and complicated 5-year environmental project is being implemented. Entitled “MedBycatch”, the project aims to reduce bycatch of vulnerable species and, having begun in 2017, it is scheduled to run until the end of this year. The project’s dual aims are, the collection of robust data on Mediterranean bycatch, and the development of the most effective and viable bycatch mitigation measures.

What is Bycatch?

The term “bycatch” refers to the incidental or unintentional capture of non-target marine species during fishing operations. Vulnerable species like sharks and rays, sea turtles, sea birds, marine mammals, corals and sponges, get trapped in fishing gear alongside “target” species – the ones the fishers want to catch.

One might ask, “Is bycatch such a serious problem that it poses a real threat to biodiversity and the balance of marine life?”

Numerous environmental NGOs have been raising the alarm, but for anyone that remains unconvinced, the annual report by the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations provides hard evidence.

More than 500,000 marine mammals (excluding polar bears and walruses) are incidentally captured (or “by-caught”) each year, and this is the main reason that the populations of some species have seriously declined and are now finding it hard to recover.

Around the world a total of 38 million tons of non-target species are unintentionally caught in fishing gear each year. That is 40% of the global fish catch! A large proportion of this catch is thrown back into the sea dead, dying, or seriously injured, while the remainder is disposed of on land. In the case of some species, the ratio of commercially valuable to unsaleable catch is truly dramatic: for every kilo of shrimp caught, between 5 and 20 kilos of bycatch can end up in the nets!

©CNN Greece, photo Lefteris Partsalis

MedBycatch

Along with other waters globally, the Mediterranean Sea suffers heavily from the bycatch issue, putting many species in danger of becoming locally extinct. The MedBycatch project launched in 2017 and is now being implemented in five Mediterranean countries, Morocco, Tunisia, Turkey, Italy and Croatia. The project follows a standardised research methodology and aims to identify which bycatch mitigation methods are most efficient, so that these can be widely adopted and applied.

The project studies different types of fishing gear, such as bottom trawl nets, longlines and gillnets, aiming to reduce the consequences of the bycatch they cause to vulnerable species.

In common with the types of gear that are towed behind vessels, static nets – that are effectively a curtain that hangs in the water – also constitute a significant threat.

©CNN Greece, photo Lefteris Partsalis

Twenty-three organisations across the Mediterranean are working together reduce bycatch in the Mediterranean through the MedBycatch project. Seven of these, namely the Mediterranean Association to Save the Sea Turtles – MEDASSET, the Specially Protected Areas Regional Activity Center of the United Nations (SPA/RAC) based in Tunis, the Birdlife Europe and Central Asia, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), The Agreement on the Conservation of Cetaceans of the Black Sea, Mediterranean Sea and contiguous Atlantic Area (ACCOBAMS), the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM/FAO) and the WWF Mediterranean Marine Initiative are coordinators of the project, which is funded by MAVA Foundation.

As Mr Anis Zarrouk, GEF Adriatic & MedBycatch Projects Officer in SPA/RAC, reveals to CNN Greece, “What is truly important about the MedBycatch Project is that, for the first time, data collection on bycatch of vulnerable species is following a standardised methodology, and that so many organisations are working together to collect robust data across the Mediterranean and to propose efficient bycatch mitigation methods.”

©CNN Greece, photo Lefteris Partsalis

Until recently, each organisation followed its own data collection protocols making comparisons particularly challenging and any conclusions unreliable. In addition to the collection of standardised and accurate data that will increase knowledge on the bycatch of vulnerable species, the MedBycatch project also works to: raise awareness on the bycatch issue among the fishing community and all key stakeholders; create the conditions in which sustainable fishing methods can be adopted, and provide training in these.

Trained observers go aboard with the fishers and stay with them during their trips, recording everything related to the fishing effort. Data concerning the total catch as well as any bycatch of vulnerable species are registered according to the project partners’ commonly agreed protocol and fed into a joint database that will allow reliable conclusions to be drawn.

Mr Hamza Ben Hlima, a MedBycatch observer, said to CNN Greece,

“All the information that we collect on board, provides valuable insights into the locations at which vulnerable species are concentrated. We can then alert fishers to their presence. These species, regardless of their commercial value, play a crucial role in marine biodiversity conservation.” Mr Hlima concludes, “Part of my mission at sea is to help fishermen with all their fishing tasks and this has led to the building of some strong and meaningful relationships. Fishers even call sometimes to give me the exact geographic coordinates of a bycaught sea turtle or dolphin.”

©CNN Greece, photo Lefteris Partsalis

Mr. Anis Zarrouk tells us that the MedBycatch observers go out to sea with the fishers from 23 ports across Tunisia and spend many hours daily registering everything related to the fishing effort. In this way they have managed to collect 2 years’ worth of data on the bycatch of vulnerable species.

“This task required mutual trust between the observer and the fisher. It’s something that took time to build, as the fishers needed to accept that the role of the observer was not to criticise but to collect data and help them” explains Mr. Zarrouk.

The MedBycatch data collection methodology includes three different approaches: On board observations by trained observers; interviews in the ports and questionnaire filling, and fisher self-reporting. In Tunisia, the MedBycatch Project is being coordinated by SPA/RAC with the collaboration of the General Directorate of Agricultural Production (DGPA), the National Institute of Marine Sciences and Technologies (INSTM) and the valuable contribution of the organisations AAO/Birdlife Tunisia (Association Les Amis des Oiseaux) and WWF Tunisia.

Mrs. Asma BEN ABDA, Head of Fisheries & Aquaculture department of the Regional Commissary for Agriculture Development of Tunis (CRDA Tunis), says that her role is to bring fishers into contact with the observers and ensure the unimpeded realisation of the project. She also conveys that she has experienced a shift in the attitude of the fishers towards the problem of bycatch of vulnerable species over the years during which the MedBycatch project has been running.

©CNN Greece, photo Lefteris Partsalis

Mr. Marouene Bdioui, Researcher at the National Institute of Marine Sciences & Technologies (INSTM) and supervisor of the MedBycatch project in Tunisia, was keen to emphasise that, occasionally, the percentage of targeted (commercially valuable) species in a catch accounts for only 20% of its total. The remaining 80% is bycatch and is thrown back, dead or alive. Some of the species that are discarded in this way are in danger of extinction.

In the National Institute of Marine Sciences & Technologies in Tunisia, testing of tools that mitigate bycatch of vulnerable species is under way, and as Mr. Bdioui explained to us, a new generation of circle hooks has been proven to reduce fatal injuries while allowing easier release. Additionally, he gave us a demonstration of how placing a special metal grid in a trawl net can prevent the entrapment of larger marine species.

©CNN Greece, photo Lefteris Partsalis

Second Phase

The MedBycatch project is currently in its second phase and is expected to conclude its activities in October 2022. The focus of the implemented activities is on the testing of different bycatch mitigation tools and methods per fishing gear and per species, using the data collected during the first phase (September 2017 – June 2020).

“There are many cases of fishers coming to share with us that they haven’t encountered a particular species for three or four years. At this point, we are conducting testing of bycatch mitigation tools and methods and when we finalise them, we will proceed with concrete proposals to the Ministry for a national bycatch mitigation strategy”, Mr. Bdioui says.

During this second phase of the project, the observers are continuing with the collection of data on bycatch of vulnerable species in Morocco, Tunisia, Turkey, Italy and Croatia, in the way previously described. Another major objective for this phase is the development of policy recommendations that will lead to effective regional and national strategies for the mitigation of bycatch of vulnerable species.

The Role of MEDASSET

Since the beginning of the MedBycatch project in 2017 and up to the present day, MEDASSET, being one of the seven organisations of the steering committee of the project, has contributed to the data collection protocol on sea turtle bycatch and the MedBycatch regional review on sea turtles; has actively participated in the training of observers on data collection and fishermen on self-reporting; has lobbied policymakers on a regional and national level regarding the problem of bycatch, and has carried out several communication activities to raise public awareness of bycatch.

MEDASSET also coordinates the data collection programme and all the project activities in Turkey in collaboration with the Turkish organisations, WWF Turkey, DEKAMER, Doga Dernegi and TUDAV .

As Mrs Nadia Andreanidou, Programmes & Policy Officer at MEDASSET & MedBycatch Project Coordinator for Turkey, reveals to CNN Greece, the goal of MEDASSET is to build on the project’s results and to promote the implementation of bycatch mitigation measures across the Mediterranean, beyond the close of the MedBycatch project.

©MedBycatch Project, photo Omar Gharbi

Alarming Facts

Over 300,000 sea birds, including 15 species of albatrosses threatened with extinction, are estimated to die each year in longlines and trawl fisheries. Additionally, an estimated 400.000 of sea birds die in gillnets each year.

Over 132,000 sea turtles are captured each year in the Mediterranean, with probably over 44,000 incidental deaths caused per year, while many others are intentionally killed.

Small vessels using set net, demersal longlines or pelagic longlines represent most of the Mediterranean fleet and likely cause more incidental or intentional sea turtle deaths than large vessels that typically use bottom trawl or pelagic longlines.

Comments are closed.